Cross-posted from my nature blog at thedyingfish.com.

I spent last year walking. If I had to give a very short account of my time that would be it.

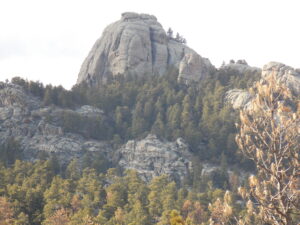

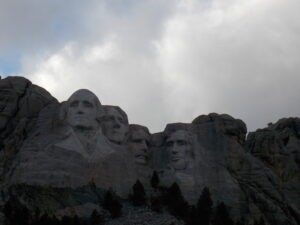

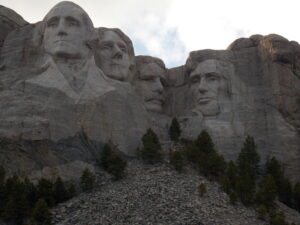

Allowed a few additional words, I would say that I drove my tiny car to the west coast early last spring, sold it, mounted a bulky pack and started walking toward Washington, DC. Among other states encountered, I crossed the endless expanse of Montana early last summer and then saw each of the Dakotas. I was in southern Minnesota when the first tantalizing hint of fall turned the first maples red. I spent time in the hardwood lowlands along the Mississippi for the first time in my life. And finally, in mid-December, I walked into Washington, DC, on the C&O Canal Towpath trail and saw where the Potomac merges with tidewater.

It was all an incredible departure from the serene and soggy hardwood forests I thrive in here in Pennsylvania. To say the very least, I got out of my comfort zone for a while. I immersed myself in places that were unpredictable to me and slept among unfamiliar creatures. And if nothing else, one might as well wander the year away in an era that has seen our rulers prohibit normalcy.

Potential sources of fear abounded when I left friends and family far behind and struck out on my own last March.

Back when I was a kid, I’d been afraid to sleep alone outside but I’d eventually taken the leap, one small adventure at a time, and this was no longer an issue when it came time to carve out a first campsite among the underbrush of the great Pacific coastal forest.

Long ago, I’d started a very long walk in Georgia and was afraid I wouldn’t be able to find places to camp along the way north. But I had found hundreds of unique places over the next few years and so, when I started making my way toward the Cascade Range last April, that was no longer a fear either.

Starting out in the west, I was afraid I wouldn’t be able to find enough water all along the way but I never really had a problem with this through Washington State and didn’t fear this anymore by the time I reached the Montana desert.

Starting near Seattle, I had some apprehension about activists of the fringe political left recognizing me as an enemy by the flag which flew above my pack. How many times would I be beaten? But after passing thousands of motorists, pedestrians and cyclists of all descriptions in my first week, this fear also subsided.

Aside from members of the rabid left, I fully expected that somewhere, across the broad swath of America, I’d run into violent people. How many murderers and otherwise mentally unstable individuals do we see constantly in the news? But after walking on through communities of all descriptions, I didn’t go on constantly looking over my shoulder.

As I went on camping in unorthodox places night after night, I worried at first about being discovered and kicked out, perhaps violently. I camped in denser than average patches of sage brush, on steep river banks and in public parks. In time, I came to just camp where I wanted, throwing up the tent fearlessly and never, across the breadth of America, having a conflict over where I slept. I even wrote a piece on hobo-style camping that ran in Backwoodsman Magazine a couple of months ago.

The most legitimate fear I suffered was a fear of traffic—a constant menace almost from coast to coast. This is perhaps the one I can point to that got no better over time; if anything it got worse as I made my way through a midwest with far narrower road shoulders than I might have imagined. This was an example of one fear that kept me alive.

In the west, I slept in rare patches of deep mossy old growth forest—really spooky stuff if you’ve ever heard of sasquatches or seen a horror movie. But the more I spent time in these dark and lush settings, the more at ease I felt.

As a younger man, I’d feared getting lost—one of the foremost concerns of wilderness survival. But my long trips through the eastern forests had quelled these fears long ago and by the time I was halfway through my Eastern Brook Trout Solo Adventure, I felt I could say that I was always lost or that I was never lost and it amounted to the same thing: I was on the move out in the woods. This mindset served me well as I crossed the nation.

Fear of the Unknown seems to be the commonality among all of these various fears and may be the great commonality of all fears. Some people try to deal with fear of the unknown, or simply fear, by remaining in close contact with what’s familiar and comfortable all the time. Some seem to deal with it through research—by trying to eliminate unknowns through hours online finding opinions and information meant to leave no more uncertainty. And some of us deal with it by exposing ourselves to those things we fear most over and over until not only the individual fears are conquered but the fearful mindset as well.

Walking head-on into the scary stuff and surviving it is what leaves us immune to fear or at least capable of operating in the face of it. Overcoming fear imparts the mindset necessary to embark on adventure, to pursue purpose and to simply get the most out of life. For me, the Long March of Liberty was all an exercise in overcoming fear, whatever else it may have been.

I read a short article recently on the reaction of some of the Pennsylvania Amish to the incipient COVID “pandemic” as it ramped up (or at least the propaganda ramped up) in 2020. Faced with some knowledge of the threat, at least the particular congregation in question decided to continue their church fellowship, the life-blood of their community. They gathered one Sunday, as churches all over the nation were closing their doors and elevating the fear, and took communion together, drinking from a common cup.

The congregation, as a whole, contracted COVID and this came with consequences. But they were soon back at work, those who’d missed any work over it, and they were largely immune, much like with other epidemics that had passed through. Insulated from the worst of the COVID propaganda pervading our “English” communities, they’d dealt with fear head-on and had prevailed. Putting lives and livelihoods on hold just hadn’t been an option.

How much do we trust in the ability of authorities to provide the safety they so readily promise? What happens when government deprives us even of the opportunity to conquer fear—the opportunity to choose this mindset? What are the trade-offs we accept when we allow fear to rule?

A man has to fight and conquer his feelings of cowardice before he can achieve perfect courage; if he has no experience and training in that kind of struggle, he will never more than half realize his potentialities for virtue.

A quotation from early in Plato’s final work, Laws