Jim Payne writes in praise of curiosity itself in his most recent adventure travel book, Chasing Thoreau. Some might begin this volume thinking they’ll enjoy a fine adventure along with Jim on the waters of the Merrimack and Concord. Others might seek out the bits of religious enlightenment concealed within. But the common thread throughout these few days on the water, as throughout the life of Dr. James Payne, is certainly curiosity.

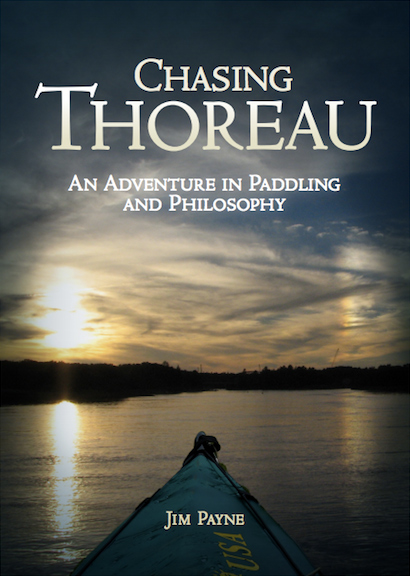

The narrative itself is simple and the goal at the outset was simple enough (though not without difficulty): retrace the route of Henry David Thoreau and his brother on their voyage down the Concord, up the Merrimack, and then down the Merrimack rivers. Jim offers us a description of these several generally fine spring days, of his “shore leave,” and of the danger and termination of the trip in turbulent tidewater. We get a glimpse of how he goes about the business of adventuring and are permitted to view just a sliver of the vigorous thought processes that act as prime mover of it all.

We who write travelogues often need a compelling story in which to inject a less marketable idea or set of ideas. It’s not clear that this was the case in Chasing Thoreau. It seems more that Dr. Payne allowed ruminations to often follow from serendipitous streamside encounters. Those encounters encompassed people from simpletons to professors and even reached the realm of plants and inanimate objects needing further study. The author’s curiosity is manifest at every bend of the river.

The grand confluence with Thoreau also arrives in the realm of curiosity. Churches and their parishioners are discussed at more than one juncture. Thoreau’s aversion to these people, or rather to their attitudes, is made manifest repeatedly in Walden. Thoreau sees these people as operating with closed minds to the broader world of religious thought as well as to the transcendentalism shared by him and Emerson. Thoreau had little use for the incurious and self-assured just as, within his lifetime, they had little use for him and his pontifications.

Jim Payne, bringing the themes of a lifetime’s research with him to the Massachusetts wilds, is skeptical of authority—this much is clear. In particular, he’s unsure whether the representatives of state and municipal authority bear any special knowledge or any higher character that would qualify them to so much as offer directions, or any special knowledge beyond what you and I hold as private citizens. Could it be that all they have is the imprimatur of authority and the almighty state? If so, why are we instinctively struck with respect for them and their opinions rather than trusting ourselves or our fellow citizens?

Toward the book’s end we see Jim tortured by strong currents—the confluence of all the waters upstream and the harbor’s tidal bore. We see Jim no less tossed about by the confluence of all the above ideas and more and their point of confluence, I might again posit, seems to be curiosity itself. The incurious parishioners of the church have found all the answers in the Bible, at least those they most wanted to find, and they’re no longer curious. There’s no need to remain curious if you’re sure to be told what to do by the representatives of the state and you’re committed to following orders. Mr. Thoreau and Mr. Payne both resolved to ply the waters of the Merrimack. And both resolved to write in praise of curiosity.

Well beyond the age of seventy at the time he launched from the banks of the Concord, Dr. Payne offers in Chasing Thoreau a brief late-life memoir on the things of great importance and on resilience, intellectual as much as physical.

To learn more and order your copy, visit chasingthoreau.com.